A Clear Look at Libertyland and Rapid City’s Crossroads

Libertyland is being sold as an exciting new amusement park that will uplift Rapid City. The marketing language is polished. The renderings are pretty. The promise is prosperity.

Behind that shine sits a very different reality. Libertyland hinges on a massive Tax Increment Financing, or TIF, arrangement that shifts risk away from deep-pocketed developers and onto local residents. It is being framed as an opportunity. In practice, it looks more like a high-gloss extraction machine aimed directly at one of America’s most beautiful and vulnerable regions.

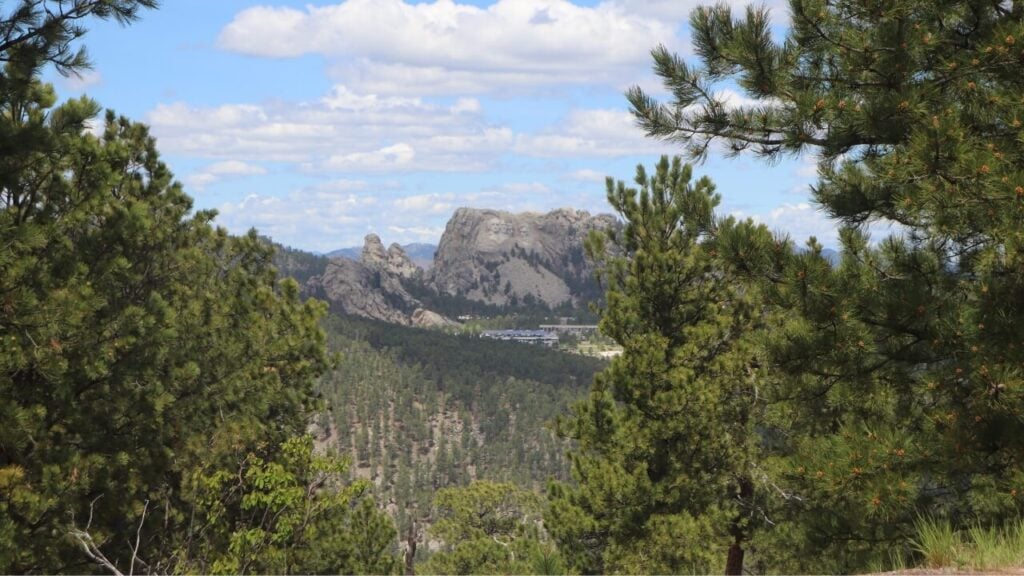

The Black Hills and Badlands are not generic backdrops for a theme park concept. They are living, breathing natural and cultural treasures. Once they are drowned in light, traffic, and noise, the loss is permanent.

What a TIF Really Means for Rapid City

TIFs are often pitched as clever tools that make big projects possible. In reality, they redirect future tax revenue to pay off private development costs. On paper, that may look like growth. On the ground, communities frequently see something else.

When TIFs go wrong, taxpayers feel it. Roads wear out. Utilities strain. Law enforcement and public services stretch thin. Residents ask why their bills creep higher while private investors walk away with steady gains. The language used is always the same: investment, progress, jobs.

In this case, Libertyland would rely on around 47 million dollars in taxpayer support. That is an enormous sum in a state with fewer than a million people. Asking residents to subsidize a private amusement park that mainly benefits out-of-state visitors is not economic development. It is dependence on corporate promises that may not age well.

The Night Skies at Stake

One issue should be enough to halt this proposal: the night skies.

The dark skies over the Black Hills and Badlands are priceless. Visitors travel from around the world to stand in quiet places and look up at a sky filled with stars, undimmed by neon or billboards. Guests on our Badlands wildlife and night sky tours consistently say that the darkness and silence are some of the most moving moments of their entire trip.

A giant, lit-up attraction along the I-90 corridor would change that forever. Light pollution does not politely stay in its lane. It spills, drifts, and washes out the very darkness people come here to find. Once that darkness is gone, it does not return.

We will have traded something rare and irreplaceable for an imitation of “fun” that can be found in countless places across the country.

A Tourist Trap Masquerading as Growth

Libertyland is being framed as a community asset. Look closer and it becomes clear who it really serves.

This project is designed to capture visitors on site and keep them there as long as possible. The goal is to ensure guests eat at Libertyland restaurants, shop at Libertyland stores, ride Libertyland shuttles, and sleep at Libertyland lodging. Every piece is engineered to keep spending inside the fence.

If you work in the tourism industry in Rapid City or the Black Hills, this matters. Guests who are sealed inside Libertyland are not spending money in your restaurant, staying in your lodging, taking your tour, or browsing your shop. You will still absorb the impacts of traffic, staffing pressures, and rising costs, but you will not share fairly in the revenue.

It is a classic captive resort model. The community takes the risk. The developer collects the reward.

The Visitor’s Regret

Picture a family planning a big day at Libertyland. They buy the tickets and an upcharge pass for rides with patriotic names. They pay for parking. They navigate crowds, lines, and upsells. By mid-afternoon, they are lighter by several hundred dollars and heavier with buyer’s remorse.

Next time, that same family will choose something different. They will drive Iron Mountain Road. They will watch bison move across Custer State Park. They will walk the Needles, swim in Sylvan Lake, sit for a sunset in Badlands National Park, and look up at a night sky that feels ancient and alive.

That is what our landscape offers. Those are the memories that bring people back.

“Progress” or Pattern?

Some will say that Libertyland represents progress. They will promise millions upon millions of dollars in economic activity. They will suggest that opposition is naïve, negative, or anti-growth.

I am not opposed to growth. I am opposed to repeating the same mistake that countless other communities have already made. I have seen charming places become uniform. Character turned into branding. Community replaced by competition. Nature reduced to landscaping around a parking lot.

This proposal is not visionary. It is not rare. It is another version of the same extractive pattern that leaves towns with higher costs, more stress, and less authenticity.

We can do better than that in South Dakota.

Asking the Peter Norbeck Question

To understand what “better” can look like, it helps to remember a name that deserves far more attention: Peter Norbeck.

Norbeck started as a well digger and went on to serve as a State Senator, Lieutenant Governor, Governor of South Dakota, and United States Senator. He earned the nickname “Honest Pete” from his work long before politics. People crossed party lines to support him because they recognized something rare: leadership that put the public first.

Look at the list of places and initiatives tied to his influence in one way or another:

These projects were bold. They were publicly minded. They created opportunities across the socio-economic spectrum and built real, lasting value for South Dakota.

Norbeck did not chase gimmicks. He built legacies.

Badlands National Park was nearly named Wonderland Park. That branding idea did not stick, and thank goodness it did not. “Badlands” tells the truth. It honors the landscape instead of dressing it up as a theme.

So the question becomes: if Peter Norbeck were alive to review Libertyland and its TIF request, what would he say? Would he see a transformative public asset, or a debt-fueled, privately owned cash machine that weakens the region’s identity?

I suspect he would shake his head and look for a better idea.

What Real Investment Could Look Like

There are better ways to improve the Black Hills and Badlands region.

Real investment would:

Strengthen existing communities and small businesses rather than trap visitors on a single property.

Protect night skies, wildlife corridors, water, and land.

Amplify Tribal Nations, local voices, and cultural heritage instead of burying them under branding.

Support year-round, livable jobs in tourism, conservation, education, and outdoor recreation.

Invite genuine public input before asking for tens of millions of taxpayer dollars.

Forty-seven million dollars is not a rounding error. It is a life-changing amount of money for a state our size. Residents deserve the chance to ask hard questions, demand clear answers, and compare this project against alternatives that might better serve the region long term.

“Is this the best we can do?” is not an unreasonable question. It is the most responsible one.

A Call for Clear Thinking and Civil Conversation

This debate will stir strong feelings, and it’s understandable. When that happens, there’s a temptation to label, attack, or dismiss. That is the moment to pause.

Strong communities don’t silence questions. They encourage research, conversation, and civic engagement. They make room for people to disagree while still caring deeply about the place they share.

Libertyland isn’t a small decision. It would shape Rapid City, the Black Hills, and our tourism economy for decades. It is worth taking the time to get this right.

Our land is rare. Our night skies are rare. Our chance to protect both is now.