Let’s dive into the tale of one of America’s most notorious Army Officers of the Black Hills, George Armstrong Custer. Custer was a man of ambition and grit, with his life journey a testament to his determination and audacity.

First off, let’s talk about his education. Custer was a graduate of the esteemed West Point Military Academy. Although he famously finished last in his class, some exploited his potential as a leader, and he did rack up some victories in the Civil War.

Fast forward a bit, and we find Custer in the Black Hills, a region rich with gold. His so-called surveying expedition into this area in 1874 in search of gold led to significant tensions with the Great Sioux Nation, escalating the conflict between the US government and the Indigenous peoples.

One of Custer’s most famous moments, however, was his defeat at the Battle of Little Bighorn, an event that has since been immortalized as “Custer’s Last Stand.” Here, Custer and his troops were outnumbered, unprepared, and outmaneuvered by a superior coalition of Native American Tribes. It was a fitting end for a man known for his ambitions, ignorance, ego, and lust for attention.

Now, let’s address the inaccuracies written after his death. It’s been said that “the victors write history,” which was undoubtedly true of Custer. While he was well known for his ambition and courage, the history books have been kind to him after his death. Many have romanticized Custer’s life story to create a hero-like narrative that whitewashes his atrocities.

Ultimately, Custer and the U.S. Government violated the Treaty of Fort Laramie, resulting in the destruction, theft, and exploitation of the Black Hills and Badlands. His actions contributed to the genocide of Native Americans, the annihilation of his men, and the most humiliating defeat of the U.S. Army in history. He should be remembered for his quest for glory rather than his long blond hair. He wore a hat to cover his thinning hair, a testament to his fragile ego.

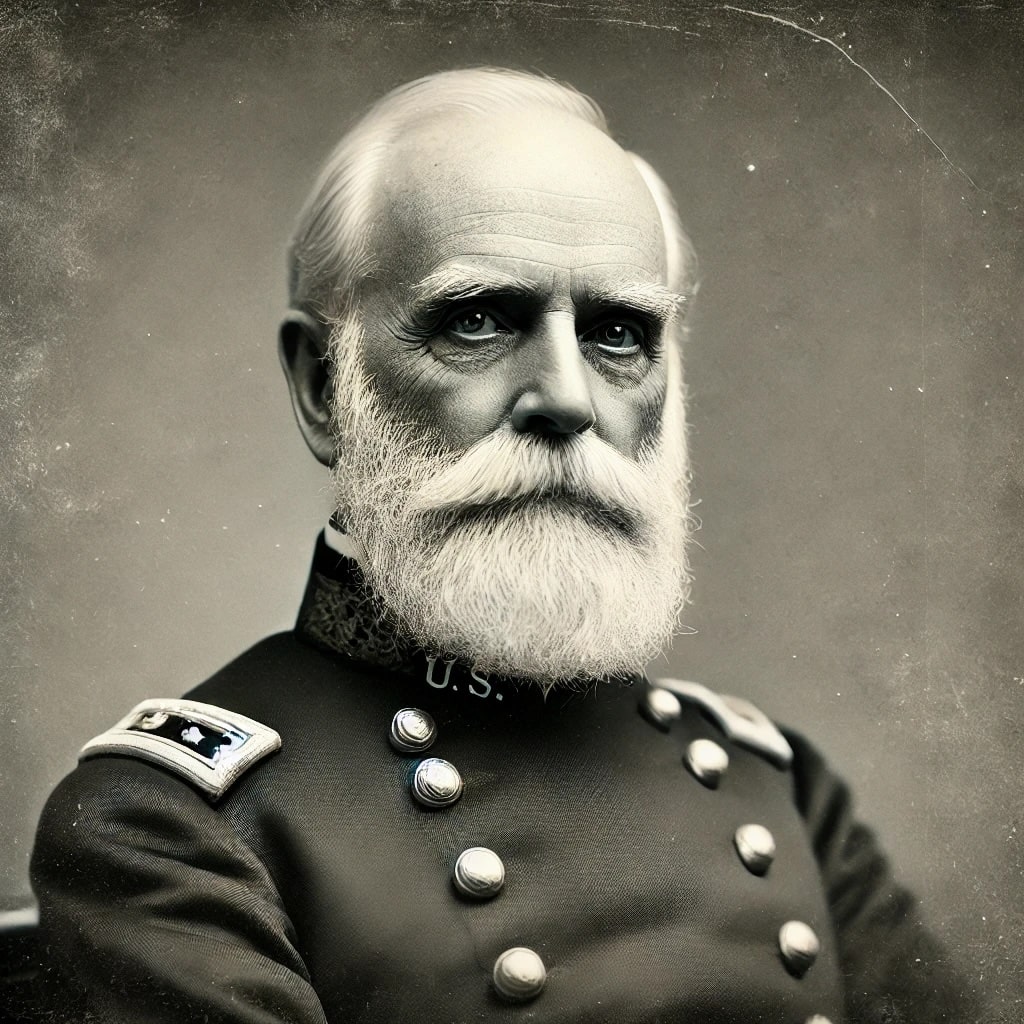

One of the most Notorious Figures of the U.S. Army is William S. Harney, an army general who served in the mid-1800s. He has been lauded for his service to the United States military—but what many don’t know is that he left a long legacy of violence and cruelty towards Native Americans.

Harney’s criminal offenses started with an incident in 1855 when his troops attacked a Sioux camp. Amidst the chaos, Harney ordered his men to fire at women and children without provocation. All told, over 300 people were killed, and the survivors were taken as prisoners of war.

Harney also played a role in creating Indian reservations, where Native Americans were forced to live in small areas with little resources or land. Harney was instrumental in helping create laws that stripped away tribal sovereignty and rights under US law.

The atrocities committed by General Harney cannot be forgotten or ignored. His legacy is one of violence, cruelty, and oppression of Native Americans—a legacy still felt today. It’s time to stop honoring him and recognize the truth about his actions so we can learn from our mistakes and work towards a brighter future for all people.

General George Crook, a notable figure in the history of the U.S. Army, left a profound impact on the Black Hills region during a period of significant conflict between the U.S. government and the Native American tribes of the Northern Plains. Known as “Three Stars” by the Lakota due to the insignia of his rank, Crook was both respected and criticized for his military strategies and his complex relationship with the tribes he fought and negotiated with. His actions, strengths, and flaws offer a nuanced portrait of a man caught in the moral and tactical dilemmas of his time.

George Crook was born on September 8, 1828, in Montgomery County, Ohio. He graduated from the United States Military Academy at West Point in 1852, ranked 38th in a class of 43 cadets. While his early performance might not have suggested greatness, his career would soon prove otherwise. Crook began his military service during the Indian campaigns in the Pacific Northwest, where he honed his skills in wilderness tactics, logistics, and survival—abilities that would later define his command style.

Crook’s time in the Black Hills is most notably tied to the Great Sioux War of 1876-1877, a pivotal conflict spurred by the discovery of gold in the Black Hills, a region sacred to the Lakota people. The U.S. government’s failure to honor the 1868 Treaty of Fort Laramie, which guaranteed the Black Hills to the Lakota, led to escalating tensions and open warfare.

Crook commanded one of the three major military columns tasked with subduing the Lakota and their allies, including the Northern Cheyenne. His campaign began with a march into the Powder River Country in Wyoming and Montana. On June 17, 1876, Crook’s forces engaged in the Battle of the Rosebud, one of the largest battles of the Great Sioux War. Although the battle was a tactical stalemate, it effectively prevented Crook from linking up with General Terry and Colonel Custer’s columns, leaving Custer’s force vulnerable at the infamous Battle of the Little Bighorn just eight days later.

Crook’s strengths as a military leader lay in his adaptability, logistical acumen, and deep understanding of wilderness combat. He was known for his ability to lead troops through harsh terrains and for maintaining discipline and morale under difficult conditions. Crook often employed Native American scouts, whose knowledge of the land and tactical prowess he deeply valued. His respect for these scouts set him apart from many of his contemporaries and earned him a reputation for pragmatism.

Despite his strengths, Crook’s leadership was not without flaws. His hesitancy to pursue aggressive action after the Battle of the Rosebud has been criticized as a missed opportunity that contributed to Custer’s isolation at Little Bighorn. Furthermore, while Crook showed a degree of respect for Native Americans, he remained a product of his time, enforcing policies that ultimately sought to displace them from their ancestral lands. His campaigns contributed to the loss of Native sovereignty and culture, a legacy that casts a shadow over his achievements

Crook’s relationship with the Lakota and other tribes was complex. While he fought against them in battle, he also advocated for more humane treatment of Native Americans. He frequently criticized the U.S. government for breaking treaties and failing to meet its obligations. After the Great Sioux War, Crook played a significant role in negotiating the surrender of the Apache leader Geronimo, an experience that further highlighted his conflicting role as both a warrior and a mediator.

After his service in the Black Hills, Crook continued his military career, focusing on conflicts with the Apache in the Southwest. His tactics in the Apache campaigns mirrored those used in the Northern Plains, relying heavily on Native scouts and emphasizing mobility and surprise. Crook’s advocacy for Native rights grew more pronounced in his later years, as he called for fairer treatment and criticized government corruption.

General George Crook died on March 21, 1890, in Chicago, Illinois. He was buried in Arlington National Cemetery, leaving behind a legacy that remains deeply debated. To some, he was a capable and compassionate leader who recognized the humanity of his adversaries. To others, he was a symbol of U.S. expansionism and the destruction of Native American ways of life.

Richard I. Dodge was both a frontier soldier and writer.

Helped establish forts to control Native movement.

Authored Our Wild Indians, portraying Indigenous people as obstacles to expansion.

His biased accounts fueled settler justification for taking the land.

Philip Sheridan brought his Civil War ruthlessness westward.

Often tied to the infamous line: “The only good Indian is a dead Indian.”

Oversaw campaigns that forced Native nations onto reservations.

Known for hard-fisted strategies that crushed resistance.

Alfred Terry was Custer’s superior during the 1876 campaigns.

Advocated caution, but ultimately approved Custer’s advance toward the Little Bighorn.

Managed Army districts that included the Black Hills.

Remembered as a bureaucratic but pivotal figure in U.S. expansion.

Nelson A. Miles built his career on relentless pursuit.

Led campaigns in the Badlands to enforce reservation boundaries.

Key figure during the Ghost Dance crisis in 1890.

While he condemned the Wounded Knee Massacre, his policies helped set the stage for it.

The darkest chapter came in December 1890.

Colonel James W. Forsyth, commanding the 7th Cavalry, attempted to disarm Big Foot’s Miniconjou Lakota at Wounded Knee Creek.

Tensions erupted, and soldiers opened fire, killing over 250 men, women, and children.

The massacre remains one of the most infamous acts in U.S. military history, worsened by the awarding of Medals of Honor to participants.

The U.S. Army figures in the Black Hills and Badlands represent both military ambition and moral failure.

They advanced U.S. expansion while breaking treaties.

They were hailed as heroes in the 19th century but are remembered today for dispossession and tragedy.

For Native nations, the Black Hills remain a sacred land, central to identity and ongoing struggles for justice.