Iron Mountain Road: The Story, The Visionaries, and the Legacy of One of the Most Beautiful Drives in the Black Hills

Iron Mountain Road is more than a scenic drive. It is a handcrafted experience built with intention, artistry, and a deep respect for the Black Hills. Every curve, pigtail bridge, and tunnel tells a story shaped by pioneers, engineers, dreamers, and workers whose devotion lives on in every mile of this remarkable roadway.

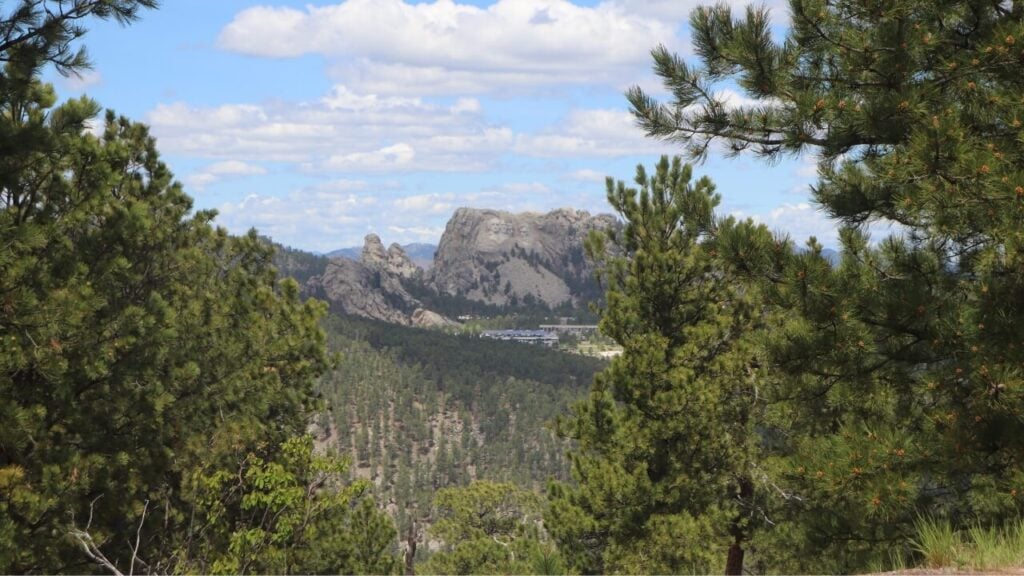

Most travelers have no idea how extraordinary its history is. They drive the spirals, glide through the tunnels that frame Mount Rushmore, and fall in love with the curves. What they experience is unforgettable. What they don’t see is the decades of passion and determination that shaped this road into something almost poetic.

This is for travelers who value meaning behind the landscape. It is a tribute to those who believed the Black Hills deserved a roadway that didn’t simply pass through the land, but introduced it with reverence.

The Birth of an Idea

In the late 1920s, Mount Rushmore was becoming a reality. Funding was secured, work was underway, and America was falling headlong into the age of the automobile. Families were traveling farther than ever, exploring places that once felt out of reach. The Black Hills, with their granite spires and ponderosa pine forests, were beginning to attract attention.

But there was a problem. The approach to the future monument didn’t do justice to the land. There was talk of building a direct road that would circle the mountain and deliver visitors quickly to the carving. It would have been practical and cheap.

It would have also been forgettable.

Two men understood the stakes and refused to settle for an ordinary solution.

The Visionaries: Peter Norbeck and C.C. Gideon

Senator Peter Norbeck and road designer Cecil Clyde Gideon were cut from the same cloth. Both adored the Black Hills. Both believed the landscape deserved a road that highlighted its character. Both understood the value of slowing down and experiencing scenery up close.

Norbeck was a grounded farm boy from Clay, South Dakota, who became an engineer, then a legislator, then a governor, and eventually a U.S. senator. He was down-to-earth, practical, and stubborn in the most admirable way. His first trip to the Black Hills was in a 1905 Cadillac Touring Car that barely made it through the journey. Between river crossings, rough routes, curious cowboys, and mechanical tinkering, he fell in love with the landscape long before tourism reached its stride.

Gideon was equally passionate about the region. He had already shaped the beloved Needles Highway with Norbeck, working alongside engineer Scovel Johnson. Together, these two believed roads should harmonize with the land rather than conquer it.

During the planning of Iron Mountain Road, Norbeck and Gideon rode on horseback through the hills, tracing old stagecoach paths, studying rock formations, and seeking a route that would evoke wonder. They passed through the forgotten remains of a once-bustling mining town. They followed deer trails. And somewhere between the quiet forest and rolling ridges, they envisioned something completely new.

A Road Built for Beauty, Not Convenience

The straightforward option was to build a simple road around Iron Mountain. It would have been faster, cheaper, and easier to maintain. But Norbeck and Gideon weren’t interested in shortcuts.

They wanted a road that would slow travelers down. They wanted visitors to breathe the scent of the pines, feel the roadside cliffs rising beside them, and experience Mount Rushmore appearing like a surprise from the heart of the hills.

In their eyes, a rushed road would cheat people of the emotional experience of arriving at the monument. Instead, they designed a route that climbed Iron Mountain itself, featuring steep grades, hairpin turns, and dramatic landscape.

It was bold. But it was beautiful.

The Tunnels That Frame a Nation

One of the most iconic elements of Iron Mountain Road is its tunnels. They are narrow, rustic, and carved with purpose. Norbeck insisted that these tunnels be oriented to frame Mount Rushmore as travelers emerged from the darkness of the rock.

Instead of a casual glimpse, the monument appears like a revelation held still in stone.

This effect required precise planning long before machinery arrived. Norbeck and Gideon chose each tunnel’s placement with artistic intention. They knew the emotional power of the reveal and designed the landscape to participate in the experience.

Today, drivers still gasp as the presidential faces appear perfectly centered in the opening ahead.

Engineering Challenges: The Birth of the Pigtail Bridges

As beautiful as the design was, the western side of Iron Mountain presented a serious obstacle. The descent was steep, too steep for a traditional road to manage safely. Norbeck also refused to use steel and concrete. He wanted wooden structures that blended into the forest.

C.C. Gideon accepted the challenge.

His solution was revolutionary: spiraling wooden bridges that loop over themselves, lifting or lowering vehicles in smooth corkscrews. These became known as the Pigtail Bridges, a whimsical and functional design that solved a difficult engineering problem.

The bridges were crafted with locally harvested timber. Builders shaped the logs by hand, fitting each beam with care. At the time, such spirals were rare, and Gideon had no guarantee they would withstand the elements long-term.

Yet the structures far exceeded expectations. They lasted more than half a century before major repairs were needed.

Their grace and ingenuity remain one of the crowning achievements of road design in the Black Hills.

The Work of the Civilian Conservation Corps

The construction of Iron Mountain Road began during the hardships of the Dirty Thirties. Drought swept across the plains, the stock market crashed, and countless families were left without income.

The Civilian Conservation Corps became a lifeline for many, and its workers played an essential role in bringing Iron Mountain Road to life. With minimal machinery, they used hand tools such as picks and shovels to carve the road into the mountain.

Photographs from the era show CCC workers sitting atop newly built pigtail bridges, proud of their work and unaware that future generations would admire it for decades.

Their efforts built more than a road. They built stability for families and communities during one of the most challenging periods in American history.

A Road That Encourages Stillness

Norbeck always believed people should slow down through the Black Hills. He had no patience for those who rushed from place to place without taking time to appreciate scenery. The winding nature of Iron Mountain Road is intentional. It nudges travelers into a slower rhythm.

There are sections of the route that remain one-way to preserve safety and the peaceful pace. One picturesque stretch lined with birch trees was named Mary Garden Way, honoring an opera singer who loved serene forest paths. Her visit and enthusiasm added a quiet footnote to the road’s early history.

Every part of Iron Mountain Road was created with the idea that travel is more meaningful when people take time to experience the land.

Experiencing Iron Mountain Road Today

Driving Iron Mountain Road today is like traveling through a living story. The road sweeps between ridges, dips into forests, curves around rock formations, and offers views that feel both surprising and familiar.

The tunnels still frame Mount Rushmore exactly as Norbeck and Gideon intended. The pigtail bridges guide travelers through spirals that feel playful and graceful. The overlooks encourage people to pause, look out over the Black Hills, and appreciate what early planners worked so hard to protect.

It remains one of the most scenic and meaningful drives in the United States.

Exploring With My XO Adventures

At My XO Adventures, we take travelers along Iron Mountain Road in comfortable 4×4 vehicles, sharing stories that bring the landscape to life. Guests learn about the tunnels’ intentions, the creativity of the pigtail bridges, and the personal journeys that shaped the route.

We stop at key overlooks, point out hidden details, and guide visitors through the experience at a relaxed pace. It is more than a drive. It is an immersion into the history, geology, and spirit of the Black Hills.

A Lasting Tribute to Imagination

Iron Mountain Road stands as a testament to creativity, cooperation, and heartfelt connection to the land. It reflects the dreams of two men who wanted the Black Hills to be shared in a way that honored their beauty. Their work continues to touch every traveler who follows the curves, passes through the tunnels, and spirals across the bridges.

The next time you explore Iron Mountain Road, take a moment to appreciate the effort, the artistry, and the devotion that built it. This road was crafted to inspire wonder, and nearly a century later, it still does.